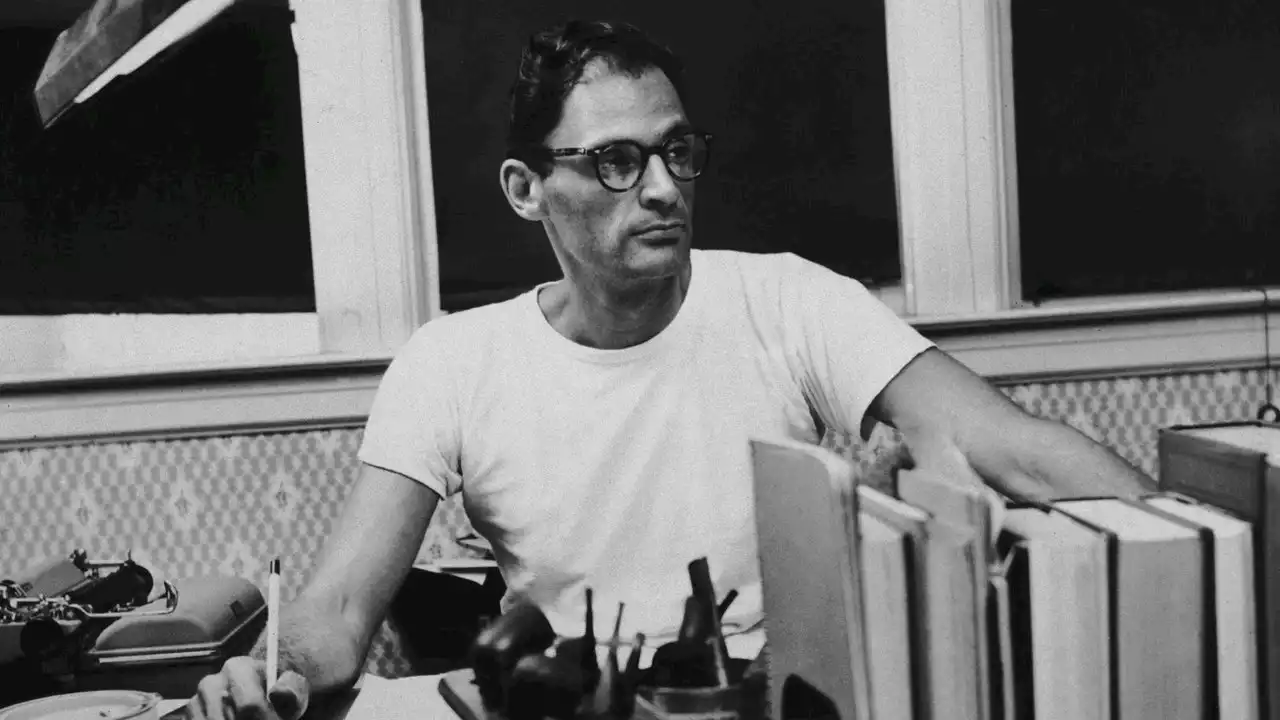

Arthur Miller shares the story behind his drama about the Salem witch trials. NewYorkerArchive

As I watched “The Crucible” taking shape as a movie over much of the past year, the sheer depth of time that it represents for me kept returning to mind. As those powerful actors blossomed on the screen, and the children and the horses, the crowds and the wagons, I thought again about how I came to cook all this up nearly fifty years ago, in an America almost nobody I know seems to remember clearly.

If our losing China seemed the equivalent of a flea’s losing an elephant, it was still a phrase—and a conviction—that one did not dare to question; to do so was to risk drawing suspicion on oneself. Indeed, the State Department proceeded to hound and fire the officers who knew China, its language, and its opaque culture—a move that suggested the practitioners of sympathetic magic who wring the neck of a doll in order to make a distant enemy’s head drop off.

The Red hunt, led by the House Committee on Un-American Activities and by McCarthy, was becoming the dominating fixation of the American psyche. It reached Hollywood when the studios, after first resisting, agreed to submit artists’ names to the House Committee for “clearing” before employing them. This unleashed a veritable holy terror among actors, directors, and others, from Party members to those who had had the merest brush with a front organization.

I visited Salem for the first time on a dismal spring day in 1952; it was a sidetracked town then, with abandoned factories and vacant stores. In the gloomy courthouse there I read the transcripts of the witchcraft trials of 1692, as taken down in a primitive shorthand by ministers who were spelling each other. But there was one entry in Upham in which the thousands of pieces I had come across were jogged into place.

As with most humans, panic sleeps in one unlighted corner of my soul. When I walked at night along the empty, wet streets of Salem in the week that I spent there, I could easily work myself into imagining my terror before a gaggle of young girls flying down the road screaming that somebody’s “familiar spirit” was chasing them. This anxiety-laden leap backward over nearly three centuries may have been helped along by a particular Upham footnote.

I was also drawn into writing “The Crucible” by the chance it gave me to use a new language—that of seventeenth-century New England. That plain, craggy English was liberating in a strangely sensuous way, with its swings from an almost legalistic precision to a wonderful metaphoric richness.

日本 最新ニュース, 日本 見出し

Similar News:他のニュース ソースから収集した、これに似たニュース記事を読むこともできます。

Barry Cryer's family share why late star hated being called a national treasureAfter King of Comedy Barry Cryer's death earlier this week, the late star's son has been sharing some hilarious anecdotes and stories with the Mirror about the quick-witted comedian

Barry Cryer's family share why late star hated being called a national treasureAfter King of Comedy Barry Cryer's death earlier this week, the late star's son has been sharing some hilarious anecdotes and stories with the Mirror about the quick-witted comedian

続きを読む »

Why DeepMind co-founder Mustafa Suleyman has quit Google to become a VCDeepMind co-founder Mustafa Suleyman surprised many of his followers last week when he announced he's leaving Google to become a venture capitalist.

Why DeepMind co-founder Mustafa Suleyman has quit Google to become a VCDeepMind co-founder Mustafa Suleyman surprised many of his followers last week when he announced he's leaving Google to become a venture capitalist.

続きを読む »

Why Matt Reeves Turned Down Directing Ben Affleck's Batman MovieMatt Reeves explains turning down directing Ben Affleck's TheBatman and rebooting with Robert Pattinson as a new Dark Knight:

Why Matt Reeves Turned Down Directing Ben Affleck's Batman MovieMatt Reeves explains turning down directing Ben Affleck's TheBatman and rebooting with Robert Pattinson as a new Dark Knight:

続きを読む »

What is the 'plate test' and why it's important in making marmaladeHow to judge if your marmalade is set by using a frozen plate.

What is the 'plate test' and why it's important in making marmaladeHow to judge if your marmalade is set by using a frozen plate.

続きを読む »

Why This Hairstyle Is the Perfect “New Year, New You” MoveWho needs resolutions when you have a transformational cut?

Why This Hairstyle Is the Perfect “New Year, New You” MoveWho needs resolutions when you have a transformational cut?

続きを読む »

Activision's version of why it sold to Microsoft doesn't add upWSJ reporter who investigated Activision employees' complaints says its CEO is spinning when he explains why the company sold to Microsoft

続きを読む »