Revisit lawrence_wright on the surgeon who became a master of terror.

Last March, a band of horsemen journeyed through the province of Paktika, in Afghanistan, near the Pakistan border. Predator drones were circling the skies and American troops were sweeping through the mountains. The war had begun six months earlier, and by now the fighting had narrowed down to the ragged eastern edge of the country. Regional warlords had been bought off, the borders supposedly sealed.

There was a telephone number on the wanted poster, but Gula Jan did not have a phone. Zawahiri and the masked Arabs disappeared into the mountains.In June of 2001, two terrorist organizations, Al Qaeda and Egyptian Islamic Jihad, formally merged into one. The name of the new entity—Qaeda al-Jihad—reflects the long and interdependent history of these two groups.

The center of this cosmopolitan community was the Maadi Sporting Club. Founded at a time when Egypt was occupied by the British, the club was unusual for admitting not only Jews but Egyptians. Community business was often conducted on the all-sand eighteen-hole golf course, with the Giza Pyramids and the palmy Nile as a backdrop. As high tea was served to the British in the lounge, Nubian waiters bearing icy glasses of Nescafé glided among the pashas and princesses sunbathing at the pool.

Umayma Azzam, Rabie’s wife, was from a clan that was equally distinguished but wealthier and also a little notorious. Her father, Dr. Abd al-Wahab Azzam, was the president of Cairo University and the founder and director of King Saud University, in Riyadh. He had also served at various times as the Egyptian ambassador to Pakistan, Yemen, and Saudi Arabia. His uncle was a founding secretary-general of the Arab League.

For anyone living in Maadi in the fifties and sixties, there was one defining social standard: membership in the Maadi Sporting Club. “The whole activity of Maadi revolved around the club,” Samir Raafat, the historian of the suburb, told me one afternoon as he drove me around the neighborhood. “If you were not a member, why even live in Maadi?” The Zawahiris never joined, which meant, in Raafat’s opinion, that Ayman would always be curtained off from the center of power and status.

Although Ayman was an excellent student, he often seemed to be daydreaming in class. “He was a mysterious character, closed and introverted,” Zaki Mohamed Zaki, a Cairo journalist who was a classmate of his, told me. “He was extremely intelligent, and all the teachers respected him. He had a very systematic way of thinking, like that of an older guy. He could understand in five minutes what it would take other students an hour to understand. I would call him a genius.

Egypt was already in the midst of a revolution. The Society of Muslim Brothers, the oldest and most influential fundamentalist group in Egypt, instigated an uprising against the British, whose lingering occupation of the Suez Canal zone enraged the nationalists.

Stories about Sayyid Qutb’s suffering in prison have formed a kind of Passion play for Islamic fundamentalists. Qutb had a high fever when he was arrested, but the state-security officers handcuffed him and took him to prison. He fainted several times on the way. For several hours, he was kept in a cell with vicious dogs, and then, during long periods of interrogation, he was beaten. His trial was overseen by three judges, one of whom was a future President of Egypt, Anwar al-Sadat.

Qutb divides the world into two camps—Islam and Jahiliyya. The latter, in traditional Islamic discourse, refers to a period of ignorance that existed throughout the world before the Prophet Muhammad began receiving his divine revelations, in the seventh century. For Qutb, the entire modern world, including so-called Muslim societies, is Jahiliyya. This was his most revolutionary statement—one that placed nominally Islamic governments in the crosshairs of jihad.

The clandestine Islamist groups were galvanized by the war, and, as Nasser had feared, their primary target was his own, secular regime. In the terminology of jihad, the priority was to defeat the “near enemy”—that is, impure Muslim society. The “distant enemy”—the West—could wait until Islam had reformed itself. For the Islamists, this meant, at a minimum, imposing Sharia on the Egyptian legal system.

The Cairo University medical school, where Zawahiri was specializing in surgery, was boiling with Islamic activism. And yet Zawahiri’s underground life was a secret even to his family, according to a recent article in the Egyptian press, which quoted his younger sister, Heba, on the subject. It was also a secret to his friends and classmates. “Ayman never joined political activities during this period,” I was told by Dr.

Schleifer encountered Zawahiri again at a celebration of the Eid festival, one of the holiest Muslim days of the year. “I heard they were going to have outdoor prayer in the Farouk Mosque in Maadi,” he recalls. “So I thought, Great, I’ll go pray in their lovely garden. And who do I see but Ayman and one of his brothers. They were very intense. They laid out plastic prayer mats and set up a microphone.

Their wedding was held in February, 1978, at the Continental-Savoy Hotel, which had slipped from colonial grandeur into dowdy respectability. According to the wishes of the bride and groom, there was no music, and photographs were forbidden. “It was pseudo-traditional,” Schleifer recalls. “Lots of cups of coffee and no one cracking jokes.”“My connection with Afghanistan began in the summer of 1980 by a twist of fate,” Zawahiri writes in his memoir.

He made several trips across the border into Afghanistan. “Tribesmen took Ayman over the border,” Omar Azzam told me. He was one of the first outsiders to witness the courage of the Afghan fighters, who were defending themselves on foot or on horseback with First World War carbines. American Stinger missiles would not be delivered until 1986, and Eastern-bloc weapons that the C.I.A. had smuggled in were not yet in the hands of the fighters.

“How can you make such a comparison?” Schleifer said. “There is more freedom to practice Islam in America than here in Egypt. And in Afghanistan the Soviets closed down fifty thousand mosques!” For Muslims everywhere, Khomeini reframed the debate with the West. Instead of conceding the future of Islam to a secular, democratic model, he imposed a stunning reversal. His sermons summoned up the unyielding force of the Islam of a previous millennium in language that foreshadowed bin Laden’s revolutionary diatribes. The specific target of his anger against the West was freedom.

Zawahiri envisioned not merely the removal of the head of state but a complete overthrow of the existing order. Stealthily, he had been recruiting officers from the Egyptian military, waiting for the moment when Islamic Jihad had accumulated enough strength in men and weapons to act. His chief strategist was Aboud al-Zumar, a colonel in the intelligence branch of the Egyptian Army and a military hero of the 1973 war with Israel.

Zawahiri later testified that he did not learn of the plan until nine o’clock on the morning of October 6, 1981, a few hours before it was scheduled to be carried out. One of the members of his cell, a pharmacist, brought him the news at his clinic. “In fact, I was astonished and shaken,” Zawahiri told interrogators. In his opinion, the action had not been properly thought through. The pharmacist proposed that they do something to help the plan succeed.

Zayat, among other witnesses, maintains that the traumatic experiences suffered by Zawahiri during his three years in prison transformed him from a relative moderate in the Islamist underground into a violent extremist. They point to what happened to his relationship with Isam al-Qamari, who had been his close friend and a man he greatly admired. Immediately after Zawahiri’s arrest, officials in the Interior Ministry began grilling him about Qamari’s whereabouts.

At a signal, the other prisoners fall silent, and Zawahiri cries out, “Now we want to speak to the whole world! Who are we? Who are we? Why they bring us here, and what we want to say? About the first question, we are Muslims! We are Muslims who believe in their religion! We are Muslims who believe in their religion, both in ideology and practice, and hence we tried our best to establish an Islamic state and an Islamic society!”Zawahiri continues, in a fiercely repetitive cadence, “We are not...

After Sadat began rounding up fundamentalists in the mid-seventies, Rahman travelled to Saudi Arabia and other Arab countries, where he found a number of wealthy sponsors for his cause. In 1980, he returned to Egypt as both the spiritual adviser and the emir of the Islamic Group. In one of his first fatwas, he decreed that a heretical leader deserved to be killed by the faithful.

Ibrahim had done a study of political prisoners in Egypt in the nineteen-seventies. According to his research, most of the Islamist recruits were young men from villages who had come to one of the cities for schooling. The majority were the sons of middle-level government bureaucrats. They were ambitious and tended to be drawn to the fields of science and engineering, which accept only the most qualified students.

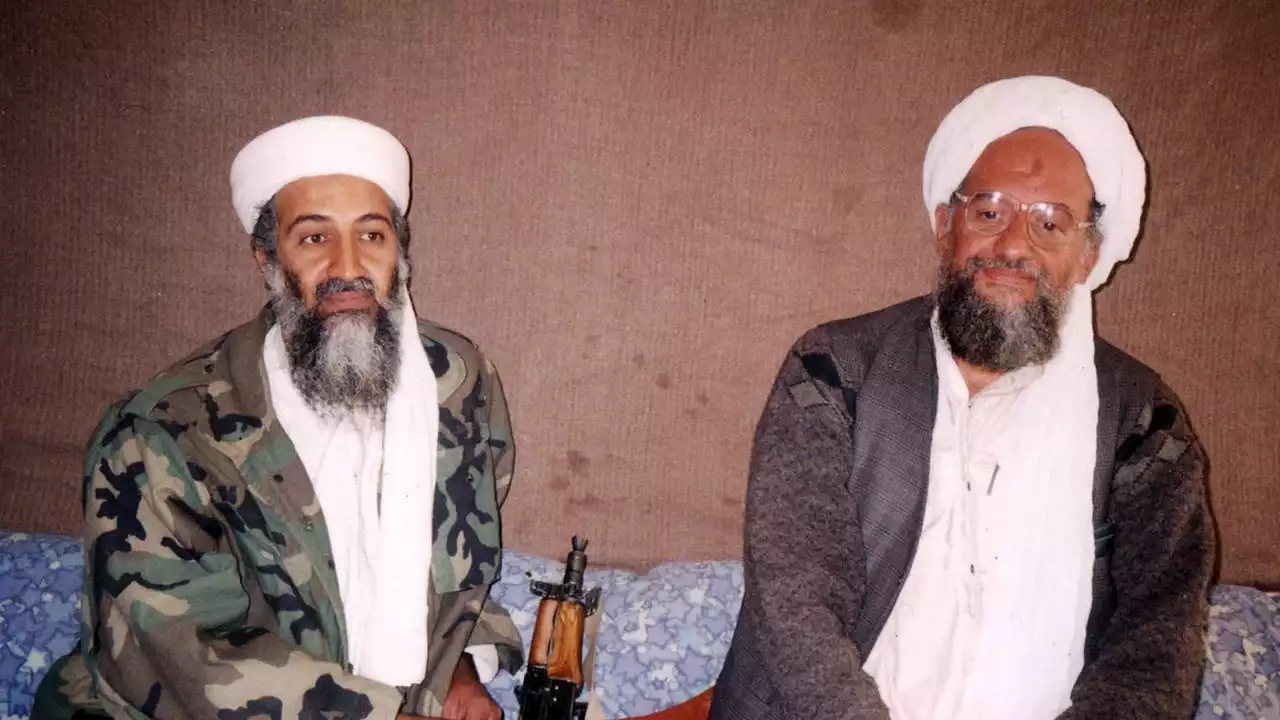

“You have the desert-rooted streak of bin Laden coming together with the more modern Zawahiri,” Saad Eddin Ibrahim observes. “But they were both politically disenfranchised, despite their backgrounds. There was something that resonated between these two youngsters on the neutral ground of faraway Afghanistan. There they tried to build the heavenly kingdom that they could not build in their home countries.

Across the Khyber Pass was the war. Many of the young Arabs who came to Peshawar prayed that their crossing would lead them to martyrdom and then to Paradise. Many were political fugitives from their own countries, and, as stateless people, they naturally turned against the very idea of a state. They saw themselves as a great borderless posse whose mission was to defend the entire Muslim people.

Unlike the other leaders of the mujahideen, Zawahiri did not pledge himself to Sheikh Abdullah Azzam when he arrived in Afghanistan; from the start, he concentrated his efforts on getting close to bin Laden. He soon succeeded in placing trusted members of Islamic Jihad in key positions around bin Laden. According to the Islamist attorney Montasser al-Zayat, “Zawahiri completely controlled bin Laden.

日本 最新ニュース, 日本 見出し

Similar News:他のニュース ソースから収集した、これに似たニュース記事を読むこともできます。

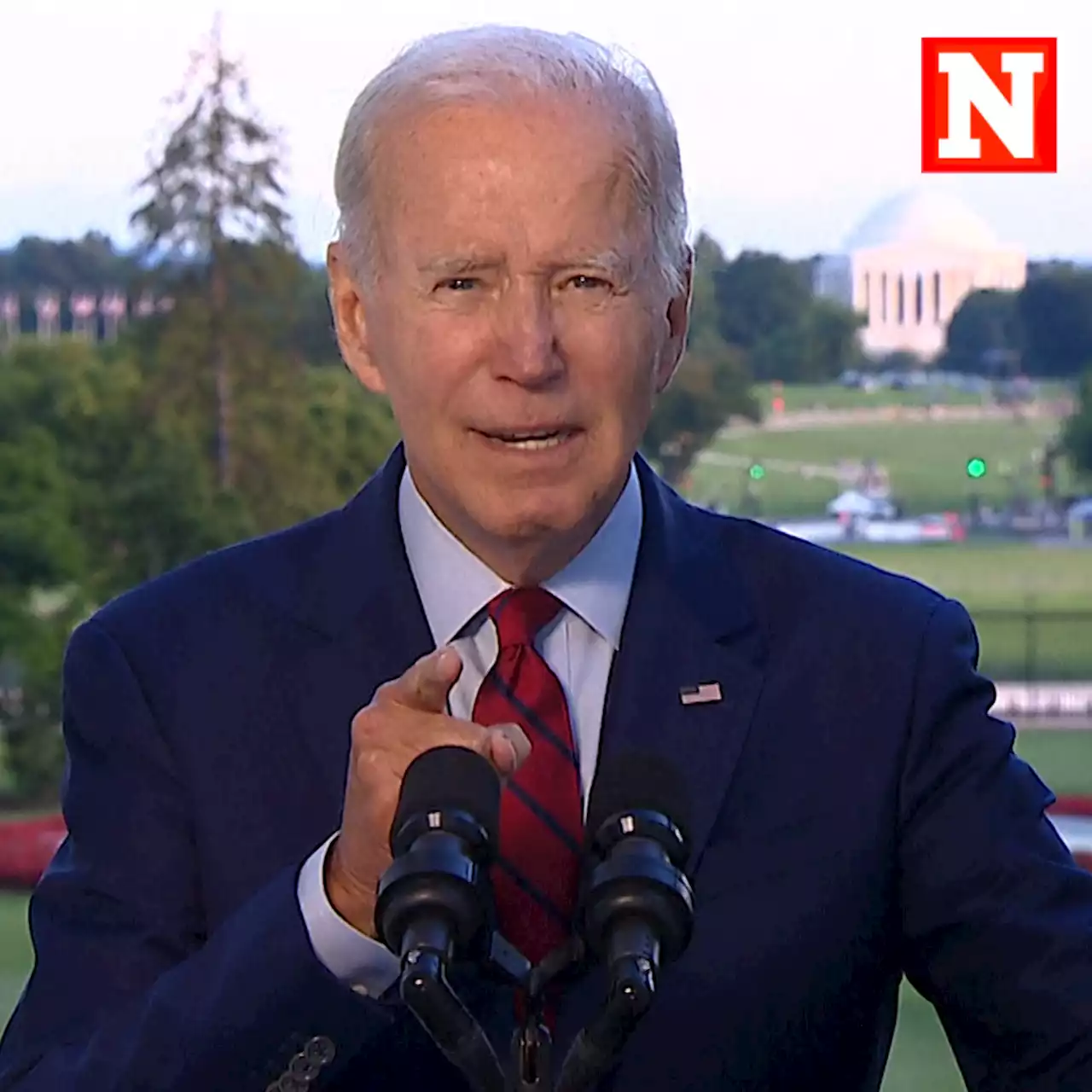

Ayman al-Zawahiri, Osama bin Laden's no. 2 man, killed by U.S.: ReportFollowing the 2011 death of bin Laden, al-Zawahiri continued to carry out the work of the terrorist network in Pakistan and Syria.

Ayman al-Zawahiri, Osama bin Laden's no. 2 man, killed by U.S.: ReportFollowing the 2011 death of bin Laden, al-Zawahiri continued to carry out the work of the terrorist network in Pakistan and Syria.

続きを読む »

Ayman al-Zawahiri, Osama bin Laden's No. 2 man, killed by U.S.Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri was killed by U.S. forces in a strike in Afghanistan over the weekend, delivering a long-sought blow to the terrorist network.

Ayman al-Zawahiri, Osama bin Laden's No. 2 man, killed by U.S.Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri was killed by U.S. forces in a strike in Afghanistan over the weekend, delivering a long-sought blow to the terrorist network.

続きを読む »

Man charged in Gurnee Mills shooting that killed 26-year-old man from Zion, police sayA 33-year-old man has been arrested for a fatal shooting in a Gurnee Mills shopping mall parking lot last November, police said Tuesday.

Man charged in Gurnee Mills shooting that killed 26-year-old man from Zion, police sayA 33-year-old man has been arrested for a fatal shooting in a Gurnee Mills shopping mall parking lot last November, police said Tuesday.

続きを読む »

Man who tried to save rafters found dead in California riverA 31-year-old man who went missing after attempting to save two rafters in distress was found dead along Northern California’s American River, authorities said.

Man who tried to save rafters found dead in California riverA 31-year-old man who went missing after attempting to save two rafters in distress was found dead along Northern California’s American River, authorities said.

続きを読む »

NY Man Pulls Loaded Gun on Pizza Delivery Driver in Order Mix-UpA seemingly run-of-the-mill pizza delivery turned violent for a Domino’s employee Saturday night suddenly facing down the barrel of a loaded firearm, police said. The delivery driver showed up to the Saugerties home, located in the heart New York’s Hudson Valley, around 10:20 p.m. for an order drop-off. Instead of the usual straight forward handoff of pizza for payment, there…

NY Man Pulls Loaded Gun on Pizza Delivery Driver in Order Mix-UpA seemingly run-of-the-mill pizza delivery turned violent for a Domino’s employee Saturday night suddenly facing down the barrel of a loaded firearm, police said. The delivery driver showed up to the Saugerties home, located in the heart New York’s Hudson Valley, around 10:20 p.m. for an order drop-off. Instead of the usual straight forward handoff of pizza for payment, there…

続きを読む »